Can you imagine being eager to repent of your sins? Are you one who would have rushed into the wilderness, hopped in your car and high-tailed it to Cameron Parish, if you’d heard that some prophet had showed up there and was baptizing people?

That sounds nice for other people. Maybe somebody else needs to go unburden themselves, but I’m okay right here. God can change a heart from anywhere, he doesn’t need me to go to Cameron parish or West Texas or Honduras to find salvation and listen to some fire and brimstone preacher. I can repent just fine right here in the quiet of my pew, without any histrionics or wailing or embarrassing outbursts. We have order – we are Episcopalians, for goodness’ sake.

But it’s not really about being Episcopalian or avoiding uncomfortable shows of emotion. It’s about fear, isn’t it? I wonder if we might be afraid of what God requires of us in judgment.

Last week at the 8:30am service, Fr. Jake preached to open the Advent season, and he relayed a striking image from a C.S. Lewis novel that opened to us the way it might look when Jesus comes to judge and cleanse us. I think it might have looked different than we expected.

So maybe that’s a good question to ask: what do we expect the exposing and purging of our sins to look like?

Did any of you see the Anne of Green Gables with Megan Follows from the 1980s? (Who didn’t?!) There’s a scene where she’s a teacher trying to inspire her drama students to really get into playing Mary Queen of Scots, and she throws herself across the stage to cling to the skirts of whoever the other character is, maybe Queen Elizabeth the First, and yells, “Save me, sweet lady!” That’s one of the first images that bursts to my mind about begging for forgiveness. The debasing oneself, the physical and figurative lowering toward the dust. T

And we can easily imagine, too, the way that we might have experienced confession and punishment growing up – a stern voice saying, “well, tell me what you did wrong.” That hot, prickly feeling on your neck and back, maybe even bowing your head in shame and sadness in this expectant silence. Perhaps there were physical consequences too, privileges removed, or pain inflicted to help teach us a lesson.

Our world judges wrong in courtrooms, with testimonies and standing up alone in the truth or in sin. We are not so far removed, only a few hundred years, from pillories and the cutting off of ears or hands.

Gosh, who would want to invite that kind of awful pain, and to be exacted from the Lord of Lords – the almighty one of ultimate power. What excruciating destruction he could bring to our lives! Surely it’s more than we could even imagine.

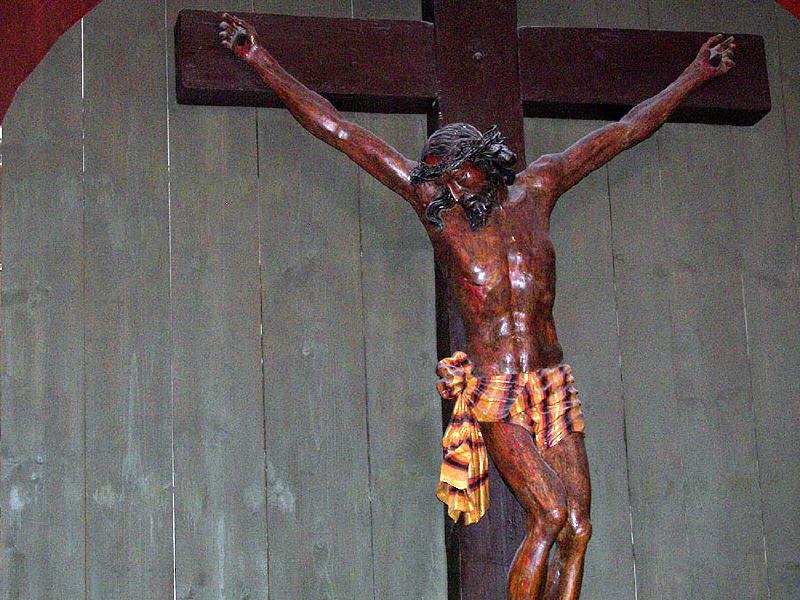

Yes, I would be one of those who would demur the invitation to go and be cleansed in the wilderness. I am not eager to have my sins nailed up next to me, or to have a scarlet letter sewn to my shirt, or to serve a sentence in a dank dungeon. Nobody really does, right?

So I wonder if the exposing and purging of our sins for Jesus’ sake might look different than what we expect. I wonder if Jesus’s redemption and facing of our faults might be surprising in view of what the world teaches us that restitution looks like.

Consider: back in the garden, when Adam and Eve had disobeyed, God sought them in the cool of the day. He didn’t come immediately the moment he knew they’d sinned. He didn’t stomp over and throw lightning bolts, he didn’t nail them up to a cross literally or figuratively, he didn’t even slap their behinds or waggle his fingers at them. With compassion and regret, he laid out the consequences of their actions; I get the sense that if it had been possible to ignore the price of their actions, he would have, but you see, they’d made a choice to not-trust God, and from that point, God still wanted to protect them as much as he could, and so the consequences provided a sort of boundary line to do what he could to keep them safe while being in the wide world.

Later, we see in the Gospels how Jesus interacts with those who come to him with humility, knowing their sins. Often these are the people who society reminds of their shortcomings all the day long. But Jesus doesn’t pile on with the cultural expectations of shunning tax collectors and ignoring prostitutes. Those who recognize their imperfections, those who are humble about their sins, those who come to Jesus holding their sins out in front of them, are received how?

Jesus looks with compassion, Jesus takes time to sit with these people. Jesus gently wipes their tears and listens to their burdens and pronounces them forgiven.

This isn’t the shunning or shaming we might expect. This isn’t the hot anger and lightning bolts that we often assume power will wield. This God revealed in Jesus Christ deals gently with those who recognize their darkness and who seek to heal from evil. And that’s the difference, isn’t it? I wonder whether the people who went out from Judea and all the surrounding countryside and who poured out from Jerusalem were the ones who knew they were already in darkness and already mired in the wilderness of sin.

I wonder whether these people who sought John the Baptist and his cleansing in the river Jordan recognized that the trip to the wilderness was really not so much geographical as it was spiritual. And that they were, in truth, already there.

Already in the wilderness. Already lost and parched. Already feeling heavy and burdened by the weight of their lives. Already wandering in guilt and regret. I wonder whether any of this feels familiar to you.

What we find in Scripture, not least in the prophecy from Isaiah this morning, is that this God, unlike rulers in the world or idols of ancient times, uses his great power when he’s doing good, not when he’s meting out consequences. The God revealed in Jesus Christ is a God of mercy, the prophet Hosea tells us, and when “he comes with might, and his arm rules for him, his reward is with him… he will feed his flock like a shepherd; he will gather the lambs in his arms.” This God is abundant in his power for mercy, for gentleness and nourishment, for forgiveness, for light and health and thriving and hope.

The powers of this world are harsh and dark and full of punishment. The consequences are dire – the wages of sin is death – but the gift of God is eternal life. God’s kingdom, the ruling order that Jesus ushers in through the incarnation, is founded on the power of God’s love, not the power of pain or punishment or shame or evil. So as we approach God’s throne of grace, our confession of sin need not be fearful or defensive. We may rest knowing that the purging of our sins will hurt only in so far as it is hard to extricate ourselves from darkness, and that the love of God is a cleansing, healing salve to our sin-sick souls.